The Rise of ADAS, AD, and ACES

Starting on the road toward fully autonomous driving

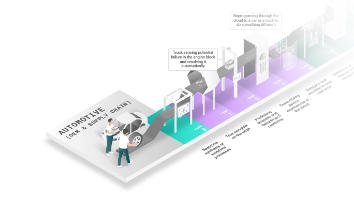

Fast-evolving advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) lead to fully autonomous driving (AD), and from there, the world races to ACES: autonomy, connectivity, electrification, and ridesharing. Collectively, these developments are poised to revolutionize all forms of transportation — and society.

Car enthusiasts often obsess over the speed at which a vehicle can accelerate from 0 to 60 miles per hour. But the gauge for the evolution from wholly unassisted to fully autonomous driving, developed by the Society of Automotive Engineers, goes from 0 to 5 only.

Speaking in broad terms, at level 0, the human is in complete control of the vehicle, managing all aspects of steering, braking, and general control. By level 1, the car may include steering or braking aids as well as adaptive cruise control or lane centering. Level 2 substitutes each “or” from Level 1 with “and,” making all mentioned devices into requirements.

At Levels 3 and 4 the vehicle is, to varying degrees, able to operate autonomously. Then, at level 5, no driver need apply — the vehicle does not need human input beyond requesting a destination.

Today, more than 60 million vehicles in the U.S. are equipped with ADAS. The percentage of total vehicles is rising rapidly, as features that were once offered only on luxury models are being included in entry-level vehicles.1

As for the widespread arrival of truly autonomous driving, the technology exists but has far to go. As Brandy Goolsby, director, Product and Solutions Marketing at Wind River®, explains, “Level 5 is being achieved within very limited scenarios only.”

Since then, the global slowdown stemming from the pandemic has significantly dented such forecasts. Yet the long-term trajectory of ADAS and AD looks virtually inexorable.

For another perspective on future growth, consider the trend lines of ADAS and AD viewed as a percentage of total automotive manufacturing costs. According to Deloitte, back in 2013 vehicle electronics averaged 18% of the total manufacturing cost. Today, the figure is 40% of total costs, and by 2030, the average vehicle’s electronics footprint is expected to represent 45% of total costs.4

As for the degree of commitment to becoming less like a traditional automaker and more like a tech company, consider just two examples from leading OEMs. Four years ago, Ford Motor Company was running a connectivity team of approximately 300 programmers. Today the number is about 4,000. Meanwhile, Volkswagen, the world’s largest vehicle manufacturer (by sales) said in 2020 that it would invest nearly $32 billion in digitization by 2025, which is double the amount it had planned on the year before.5

Intelligent Systems Research: Automotive

Find out how your peers are building and deploying intelligent systems.

Automotive Intelligent Systems Blueprint

Explore our infographic showing the results of research into the intelligent systems journey.

Podcast with Ford’s Matt Jones

Listen to the Forbes Insights “Futures in Focus” podcast with Ford’s Director of Global Technology Strategy Matt Jones.